« A-t-on jamais bien su d’où vient l’usage, si répandu en Angleterre et en Amérique, de l’envoi des “Valentines” entre jeunes gens et jeunes filles ? »

En 1882, c’était encore avec un regard éloigné qu’on observait en France les pratiques anglo-saxonnes de la Saint-Valentin. L’auteur de cet article de La Nouvelle Lune, correspondant de la revue à New York, distingue aux États-Unis parmi ces envois du 14 février les cadeaux de bon goût de la « bonne société », et les cartes commerciales vulgaires, « comiques », des classes populaires. Et d’ajouter :

« Tous les ans, les journaux américains recommencent de nouvelles études et recherches historiques sur cet usage. »

Cette dernière observation reste valable : à coups de courts articles, on voit toujours fleurir annuellement des explications sur les « origines » de la célébration de la fête des amoureux – qui désormais, sous la forme de cadeaux et de dîners, touche également l’Hexagone. Ces explications reprennent en boucle un nombre relativement restreint d’éléments, dont la valeur historique est extrêmement inégale.

La coutume viendrait d’abord d’Angleterre. Saint Valentin lui-même aurait pratiqué des mariages avant d’être martyrisé, et/ou aurait été promu par quelque pape patron des amoureux. Par ailleurs, une croyance indique que les oiseaux se reproduisent le 14 février. La date coïncide avec une fête romaine, les Lupercales, lors desquelles, notamment, les jeunes femmes étaient fouettées pour favoriser leur fécondité. Les mieux informés mettent en avant la poésie de la fin du Moyen Âge, notamment celle de la cour anglaise ou du duc de Bourgogne, célébrant au XVe siècle l’amour courtois précisément à la Saint-Valentin.

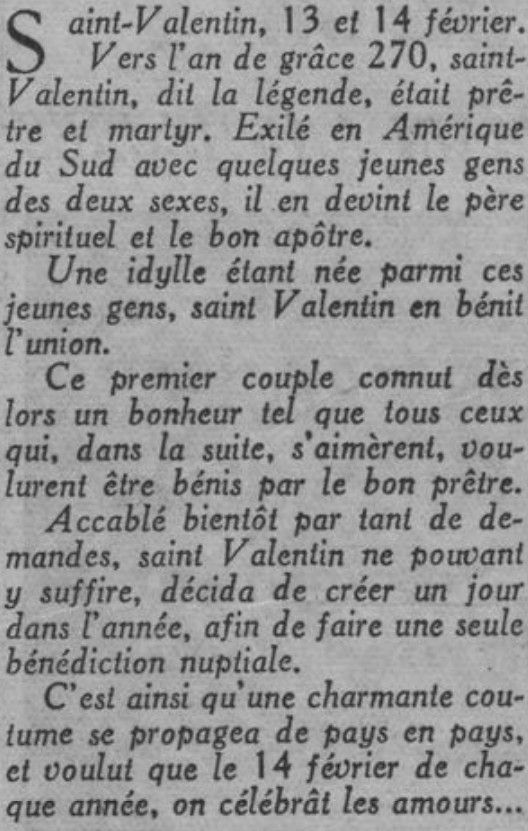

Le plus souvent cependant, la collecte d’affirmations sans réelle source et sans méthode conduit à la perpétuation de mythes, voire au non-sens historique. La chose n’est pas nouvelle. L’exemple le plus caricatural que j’ai rencontré date de la veille de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, lorsque les fleuristes commencèrent à tenter d’implanter la coutume à Paris. Alors que l’un d’eux, avenue Victor Hugo, s’offrait une publicité dans Le Journal du 13 février 1939, un petit texte indiquait à côté que saint Valentin avait patronné des mariages alors qu’il était exilé en Amérique du Sud… au IIIe siècle (c’est-à-dire 1 200 ans avant Colomb).

"Ist eigentlich bekannt, woher der in England und Amerika so weit verbreitete Brauch stammt, "Valentines" zwischen jungen Männern und Mädchen zu verschicken? »

Im Jahr 1882 wurde der angelsächsische Brauch des Valentinstages in Frankreich noch mit Argusaugen beobachtet. Der Autor dieses Artikels in La Nouvelle Lune, Korrespondent der Zeitschrift in New York, unterschied zwischen den geschmackvollen Geschenken der "guten Gesellschaft" und den vulgären, "komischen" Visitenkarten der Arbeiterklasse in den Vereinigten Staaten. Er fügte hinzu:

"Jedes Jahr beginnen die amerikanischen Zeitungen aufs Neue mit historischen Studien und Recherchen zu dieser Verwendung. »

Diese letzte Beobachtung ist nach wie vor gültig: Noch immer erscheinen jedes Jahr kurze Artikel mit Erklärungen zu den "Ursprüngen" des Festes der Liebenden - das nun in Form von Geschenken und Abendessen auch Frankreich erreicht. Diese Erklärungen wiederholen immer wieder eine relativ kleine Anzahl von Elementen, deren historischer Wert extrem uneinheitlich ist.

Der Brauch soll seinen Ursprung in England haben. Der heilige Valentin selbst soll vor seinem Martyrium Ehen geschlossen haben und/oder von einem Schutzpatron der Liebenden gefördert worden sein. Es gibt auch einen Glauben, dass Vögel am 14. Februar brüten. Das Datum fällt mit einem römischen Fest, den Lupercales, zusammen, bei dem u.a. junge Frauen ausgepeitscht wurden, um ihre Fruchtbarkeit zu fördern. Die am besten Informierten heben die Poesie des späten Mittelalters hervor, insbesondere die des englischen Hofes oder des Herzogs von Burgund, der die höfische Liebe im 15. Jahrhundert genau am Valentinstag feierte.

Meistens jedoch führt das Sammeln von Behauptungen ohne wirkliche Quelle oder Methode zur Verewigung von Mythen oder sogar zu historischem Unsinn. Dies ist nichts Neues. Das karikativste Beispiel, das mir begegnet ist, stammt vom Vorabend des Zweiten Weltkriegs, als Floristen versuchten, den Brauch in Paris zu etablieren. Während einer von ihnen, avenue Victor Hugo, am 13. Februar 1939 eine Anzeige in Le Journal schaltete, stand in einem kleinen Text daneben, dass der Heilige Valentin im Exil in Südamerika Hochzeiten gefeiert hatte... im 3. Jahrhundert (also 1.200 Jahre vor Kolumbus).

"Has it ever been well known where the custom, so widespread in England and America, of sending "Valentines" between young men and girls comes from? »

In 1882, the Anglo-Saxon practices of Valentine's Day were still observed in France with a distant glance. The author of this article from La Nouvelle Lune, the magazine's correspondent in New York, distinguishes in the United States among these February 14 shipments the tasteful gifts of "good society", and the vulgar, "comical" business cards of the working classes. And to add :

"Every year, American newspapers begin new studies and historical research on this usage. »

This last observation is still valid: short articles are still being published every year with explanations about the "origins" of the Lovers' Day celebration - which now, in the form of gifts and dinners, also reaches France. These explanations repeat over and over again a relatively small number of elements, whose historical value is extremely uneven.

The custom would come first from England. Saint Valentine himself would have practiced weddings before being martyred, and/or would have been promoted by some patron pope of lovers. There is also a belief that birds breed on February 14th. The date coincides with a Roman festival, the Lupercales, when, among other things, young women were whipped to promote their fertility. The best informed people highlight the poetry of the late Middle Ages, especially that of the English court or the Duke of Burgundy, celebrating courtly love in the 15th century precisely on Valentine's Day.

Most often, however, the collection of assertions without any real source or method leads to the perpetuation of myths, or even to historical nonsense. This is nothing new. The most caricatural example I have encountered dates from the eve of the Second World War, when florists began to try to establish the custom in Paris. While one of them, avenue Victor Hugo, was advertising in Le Journal on February 13, 1939, a small text indicated next to it that Saint Valentine had patronized weddings while he was exiled in South America... in the third century (that is to say 1,200 years before Columbus).

Source: RetroNews

Document généré en 0.06 seconde